Are you dreading the holiday season? For people with strained or estranged relationships with family members, the holidays can feel like salt in a wound. The holiday season can bring up feelings of dread, anxiety, and guilt. Perhaps you are estranged from family and experience intense guilt and grief for not celebrating with them. Perhaps you are not estranged, but the relationship feels plagued by criticism, obligation, and tense, hostile disagreements. If holiday gatherings feel tense and stressful rather than celebratory, this article is for you. 1. Get in touch with what you want. The noise of others' expectations can make it difficult to know what we want. Try journaling, talking to a therapist, or talking with a trusted friend. Maybe you want to spend the holiday with friends. Maybe you want to spend it with your family and need to put boundaries in place for your emotional safety. Maybe you want to spend the day hiking, volunteering, or doing something totally unrelated to the holiday. Think of this as a brainstorming exercise. Be mindful of thoughts like "I can't do that because so-and-so will be upset." Focus on what feels appealing to you and allow thoughts about what others will think or how they will react to float by like leaves on a stream. 2. Put social media and pop culture in context. If we look at social media posts as representations of reality, it seems all or most of our friends are having idyllic family get-togethers where everyone seems to be feeling great, close, and connected. The same goes for the endless marketing campaigns showing happy families gathering together. Given the over-representation of happy, uncomplicated family relationships in media, it makes sense if you feel like you are the only one with difficult, complicated family relationships. Remind yourself that people are less likely to be open about their struggles than their happy moments. Remind yourself that tense, anxious moments at the dinner table do not sell products, and as such we are rarely exposed to family conflict in pop culture and advertising. You are not alone in having a complicated relationship with your family, nor are you alone in having mixed feelings about the holidays. 3. Practice being open about your feelings with trusted people. While being open about our feelings can be intimidating and scary, it is an opportunity to connect and be understood. This isn’t to say you should feel like you must share your feelings at every opportunity, or with everyone. It is perfectly okay to be selective about sharing your vulnerabilities. That said, when you take the risk to share, you might find there are others in your social circle who feel similarly. If talking to people you know currently feels emotionally unsafe, consider seeking out a therapist or a support group either online or in-person. 4. Practice self-care. I am sure we are all tired of hearing the term “self-care.” To be clear, self-care does not have to be expensive, fancy, or lengthy. Practicing self-care is especially important when you are preparing to attend a potentially stressful event or unwind after one. Self-care looks different for everyone. Maybe you feel soothed by a bath or shower, a long walk, blasting music in your car, or calling a supportive friend. If possible, try scheduling time for self-care before and after an event. You can even plan to take breaks during the event, such as going for a walk or stepping away to listen to a favorite song. 5. Know your boundaries and communicate them. You are not mean, selfish, or bad for having limits and saying no. Someone having a reaction to your boundary does not mean it was wrong to set it or that you must walk it back. Here are a few examples of boundaries: “I am unable to attend the full gathering this year. Here is when I am available to visit.” “I am uncomfortable discussing this topic. Let’s change the subject.” “I am not okay with comments about my body or how much I am eating. I will have to leave if this continues.” Of course, there is so much more to handling difficult relationships than the five tips contained in this article. I hope these tips can add to the tools in your toolbox to handle the holiday season.

0 Comments

Many folks come to my website because I am a "religious trauma therapist." What does that mean? It means I work with people who are unpacking their experiences with fundamentalist, authoritarian religion. I am most experienced with the Christian Protestant evangelical homeschooling (and home-churching) movement, and I have also worked with folks from Jehovah's Witness, Mormon, Roman Catholic, and Islamic backgrounds. Being a religious trauma therapist does not mean I am anti-religion, nor does it mean the goal of therapy is for people to no longer hold religious beliefs. Many clients continue to identify with their religion in some form after therapy. My approach to religious trauma therapy is to view our time together as a space to rewrite the story of your relationship with religion, and to notice how it has impacted your relationship with yourself and others. It is a place to unpack the binary thinking that is often central to fundamentalist religion. It is about creating space to explore what does and does not fit for you, without judgment. If you were raised in a fundamentalist religion, you have had more than enough of people deciding things for you, telling you how you should and should not feel, and telling you what is right or wrong- even when it went against what you felt deep down in your core. I strive to make our space one where you feel supported in tuning into that "deep down" part of yourself. So, what is fundamentalism anyway? According to the Oxford Dictionary, Fundamentalism is "a form of a religion, especially Islam or Protestant Christianity, that upholds belief in the strict, literal interpretation of scripture." While writing this, I realized definitions are an example of fundamentalism. This is literal definition of fundamentalism, yet it does not fully capture the nuances of fundamentalism, nor does it capture what it feels like to question a fundamentalist belief system. It is also worth noting that some people are quite satisfied in a fundamentalist belief system and may never experience symptoms of religious trauma. Religious trauma symptoms tend to arise out of a two-fold event: an indoctrination into AND a subsequent breaking away from a strict set of beliefs. I tend to see clients who are in some form of the "breaking away from." Folks who do not experience the "breaking away from" are unlikely to find themselves searching for religious trauma therapy. But I digress! 4 Characteristics of a Fundamentalist Belief System This is not an exhaustive list by any means! 1. Binary Worldview. Binary thinking is not unique to fundamentalist religion. However, you may notice it is present to a greater degree in fundamentalist religion compared to other religion. Themes of "believers and non believers," "sinners/not sinners," "good/bad," "right/wrong," "men's roles/women's roles" are common. As visual, it is like everything is in stark contrast, and members are expected to adhere to these binaries. 2. "No Such Thing as a Welcome Question." Questioning is discouraged in fundamentalist belief systems, which makes sense given the binary worldview. When things are a simple yes/no or right/wrong, debating is seen as unnecessary at best and a sign of dissent at worst. When you asked questions, you may have had your status as a believer called into question in return. 3. Suspicion of outside ideas and people. In my experience, this characteristic has one of the greatest and most painful impact on religious trauma survivors. Fundamentalist families tend to isolate their children from people outside the religion. Many of my clients were homeschooled, which makes sense because many fundamentalist families turn to homeschooling to gain more control over information flow and social connections. This leaves the survivor isolated if they begin to question the fundamentalist beliefs, because the suspicion of outside ideas and people has left them surrounded by others who hold the same fundamentalist beliefs. 4. Fear-based, sometimes apocalyptic, thinking. Fundamentalist families typically hold fear-based beliefs that underlie the decision to isolate. It is common for fundamentalist beliefs to include strong apocalyptic beliefs or beliefs about hell. These fear-based beliefs can lead to intense anxiety for both the children and parents when children grow into adolescence and young adulthood, during which exploration of self and the world are key tasks of development. If you grew up in a fundamentalist belief system and struggled with transition to adulthood, you are not alone. How does religious trauma therapy help? People come to religious trauma therapy for all kinds of reasons and with all kinds of goals. Therapy has proven benefits for improving binary (polarized) thinking, anxiety (fear-based) thinking, and for improving relationships. Working with a religious trauma therapist means you have the benefit of working with someone who understands the specific issues unique to religious trauma. Put informally, the anxiety hits different when it comes from a fear of eternal punishment. Social anxiety hits different when you were taught to be suspicious of peers. Body image issues hit different when you internalized purity culture. And perhaps most importantly, learning to trust yourself is a whole different challenge when you were taught you were inherently bad and that someone else had all the answers. Everyone's therapy journey looks different. Think of these as possibilities, not guarantees, and certainly not as the "right way." Here are some things that might change for you as you heal from religious trauma:

I hope you found this article useful or relatable in some way. You deserve to heal, and you deserve to live the life you've dreamed of living. And if you're in a space where you are not quite sure what you want, but you have a sense deep down that you want to know, I want you to know support is available if you want to explore and get to know yourself. Thank you for reading. Warmly, Easin Beck, MFT Trigger Warning: Child Abuse (all forms), Domestic Violence “In general, the diagnostic concepts of the existing psychiatric canon, including simple PTSD, are not designed for survivors of prolonged, repeated trauma, and do not fit them well. The evidence reviewed in this paper offer strong support for expanding the concept of PTSD to include a spectrum of disorders, ranging from the brief, self−limited stress reaction to a single acute trauma, through simple PTSD, to the complex disorder of extreme stress that follows upon prolonged exposure to repeated trauma.” -Judith Herman, “Complex PTSD: A Syndrome in Survivors of Prolonged and Repeated Trauma." p. 388 These words were published in 1992. Here we are, thirty years and almost 3 editions of the DSM later, and Dr. Herman’s words still apply. Complex trauma survivors are STILL not represented in the DSM. Buckle up, because we are about to explore the frustrating and baffling exclusion of C-PTSD from DSM, and it's going to be almost as long as preambles to banana bread recipes. If you have complex trauma and are baffled because someone diagnosed you with... not that... this article is for you. What is the DSM?If you do not know, the DSM is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders and is put together by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). The DSM is the standard diagnostic manual used in the United States. If you pay for therapy using insurance, your therapist is required to put a DSM diagnosis in order to bill your insurance. As of 2022, therapists are required to provide a diagnosis on your Good Faith Estimate even if you pay via cash or credit card. To be open about my own perspective, I find the DSM to be problematic for many reasons in addition to the exclusion of C-PTSD which would take many more posts to explain, though the linked article is a decent introduction to the problems. It is worth noting that C-PTSD is acknowledged in another manual: the ICD. The International Classification of Diseases includes C-PTSD as a diagnosis distinct from PTSD. The distinguishing factors are that C-PTSD includes three additional types of symptoms on top of the regular PTSD criteria. The additional symptom clusters are:

Side note, my undergraduate degree was geography, and it surprises me very little that there would be a major discrepancy between the American version of something and the rest of the world’s version… but we will save that discussion for another day. So what is complex trauma? Why does having a diagnosis matter?C-PTSD, also known as complex trauma, is a trauma disorder. It impacts an estimated 1 in 25 people, and it results from prolonged or repeated interpersonal abuse. The term was by Judith Herman in the 1980s, and Dr. Herman further elaborated on the condition in 1992 in her paper “Complex PTSD: A Syndrome in Survivors of Prolonged and Repeated Trauma.” Dr. Herman’s research focused on people who survived “prolonged, repeated victimization” such as survivors of domestic violence and child abuse. She noted important differences between survivors of childhood trauma and survivors of trauma that occurred in adulthood. One of the important differences is that C-PTSD impacts interpersonal relationships more strongly than PTSD, and it seems to be linked to the nature of the trauma. For example, a car crash might lead to PTSD, but it would be unlikely to lead to C-PTSD. It is important to note that treatment needs are different for C-PTSD vs. PTSD. I like examples, so here are examples to keep in mind as we discuss why these different types of trauma require different treatments. 1. A person survives a hurricane. They lost all of their possessions, their pets, and they feared for their life during the event. This person might develop PTSD. They might experience intrusive memories and thoughts of the event, avoid places that remind them of the event (perhaps the news, old friends, etc.), experience mood changes (which could incidentally impact relationships), and experience hypervigilance (jumpiness, difficulty sleeping, anxiety). 2. A child grows up in an area with high levels of gun violence. Their parents fight frequently, and sometimes they even observe physical violence between their parents. The child is also sexually abused by a trusted family friend. This child might grow up to experience C-PTSD. In addition to typical PTSD symptoms, the child might also experience difficulty maintaining relationships, emotion dysregulation, chronic feelings of guilt and worthlessness, somatic symptoms, and chronic suicidal thoughts (could be passive or active). These are of course highly reductionist examples, but they illustrate a major difference between C-PTSD and PTSD that impacts treatment. C-PTSD impacts us relationally. Yes, relationships can be impacted by PTSD, but this is typically secondary to the symptoms. PTSD symptoms can be disruptive to relationships. Reducing the symptoms using trauma-focused therapies such as trauma-focused CBT (Prolonged Exposure, for example) will typically improve relationships. In C-PTSD, however, disruption in relationships is primary. With prolonged, repeated, interpersonal trauma, there is a loss of trust in self and others. Healing from C-PTSD requires more than processing a one-time event. It requires processing deep-seated feelings of guilt and worthlessness and building trust in ourselves. It requires building safe, supportive relationships. Another way to put it: PTSD is a disruption in feeling safe in the world. There is typically a sense of safety to regain. For survivors of C-PTSD, particularly if the trauma occurred during childhood, it may be difficulty to identify a time where the world felt safe and trustworthy. The healing can feel something like baking from scratch. For this reason, C-PTSD may require longer-term work, and it does not seem to respond to medications in the same way as PTSD. This makes a lot of sense. Medications can reduce symptoms, but they cannot teach us how to recognize and function in loving, supportive relationships. Of course, there is also the issue that because C-PTSD has only recently become a diagnosis (in ICD-11 only), so there has been little opportunity to run controlled trials to find out the most optimal treatments for C-PTSD. Because the presentation and core issues of complex trauma are different from those of PTSD, people with complex trauma often have an incorrect diagnosis, no diagnosis, or a long list of diagnoses that would be better summarized by a complex trauma diagnosis. This is problematic for many reasons, but I feel this would require a separate article. Wait, so why the fuck is it not in the DSM? You still have not explained.Here is my opinion: It makes no goddamn sense. It is a convoluted mess. In graduate school, I took every trauma class I could fit into my schedule, and we did a deep dive on this topic. I still cannot quite put it into words, but I will do my best to condense what I was able to verify via an absolute clusterfuck of online articles. So. There was a “Complex Trauma Task Force” that attempted to have C-PTSD or “developmental trauma” added to the DSM-5. The subcommittee of the Trauma, Stress and Dissociative Disorders Sub-Work Group for DSM-5 was headed by Matthew Friedman, PhD. You can read more about Dr. Friedman on his webpage, which I will put in the references because it will not allow me to insert it as a link here. I find it interesting that Dr. Friedman was highly involved with the VA. One could speculate that because his background is working with veterans, he is most highly experienced with adulthood-acquired trauma. I am not implying it is a bad or negative thing that Dr. Friedman is involved with the VA, but I do think it is worth considering that his focus does not seem to be developmental trauma. It makes sense he would have a different outlook and perspective from Dr. Judith Herman, who worked closely with complex trauma survivors. What I gather from reading over the exclusion is that it ended in a Catch-22. Dr. Friedman’s subcommittee argued that there was not enough evidence for C-PTSD to include it in the DSM-5. The Complex Trauma Task Force argued that without C-PTSD being a diagnosis, it was difficult to acquire funds needed to conduct the breadth of research the Trauma, Stress and Dissociative Disorders Sub-Work Group wished to see. According to the VA website “there was too little empirical evidence supporting Herman's original proposal that this was a separate diagnosis.” Dr. Friedman instead suggested “complex trauma” is a “dissociative subtype” of PTSD and did not warrant a separate diagnosis. Dr. Friedman suggested there was not enough evidence to suggest complex trauma would not also respond to Cognitive Processing Therapy and Prolonged Exposure, which are evidence-based treatments for PTSD. However, it does not seem that these modalities have been tested specifically with C-PTSD (and how can they be tested if there are no clear diagnostic criteria differentiating C-PTSD from PTSD?). It is worth noting that much of what distinguishes C-PTSD from PTSD in the ICD is similar to the criteria for BPD: difficulties with interpersonal relationships, suicidal thoughts, and difficulties with emotion regulation. We should absolutely reduce stigma for all neurodivergences, including BPD, so I'm not going to say "Oh we should not diagnose people with BPD because of stigma." Let's reduce stigma for people with BPD rather than pretending BPD does not exist. That said, people whose symptoms are explained well by ICD's Complex Trauma diagnosis are often misdiagnosed with BPD. If PTSD is a sufficient diagnosis for people with C-PTSD, then why are many misdiagnosed with BPD? Rhetorical question of course. While the emotion regulation skills that are inherent to BPD treatment are useful for PTSD, there is no guarantee someone diagnosed with BPD will be given the opportunity to process the underlying trauma. For obvious reasons, this is problematic, and people with C-PTSD have a right to treatment for the actual reasons they came for treatment. Hope and HealingThe good news is, there are clinicians who think outside the box of the DSM. There are treatments that target the mind-body connection and the relational issues at the core of C-PTSD. There IS research about C-PTSD, even if it isn't the type of research the subcommittee wants to see to add the diagnosis. There Dr. Herman's research, and there is the Kaiser-Permanente ACEs research, which is so validating if you are in doubt about how developmental trauma may have impacted you. There are empowering books such as Pete Walker's From Surviving to Thriving. There are therapists who work effectively with survivors of complex trauma. And there are supportive communities on social media. Complex trauma is real. It is not in your imagination, and it does carry different challenges from PTSD. Most importantly, you are not alone in the having of C-PTSD, and you will not be alone in the healing from it. Additional ReferencesBredström, A. Culture and Context in Mental Health Diagnosing: Scrutinizing the DSM-5 Revision. J Med Humanit 40, 347–363 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-017-9501-1

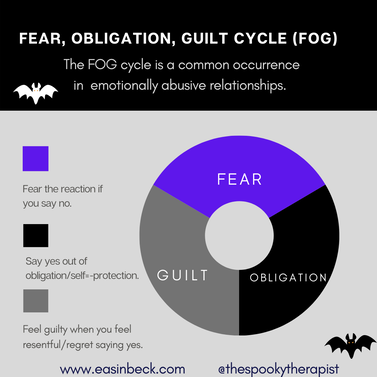

Bremness, A., & Polzin, W. (2014). Commentary: Developmental Trauma Disorder: A Missed Opportunity in DSM V. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry = Journal de l'Academie canadienne de psychiatrie de l'enfant et de l'adolescent, 23(2), 142–145. Cloitre, M. (2020). ICD-11 complex post-traumatic stress disorder: Simplifying diagnosis in trauma populations. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 216(3), 129-131. doi:10.1192/bjp.2020.43 Cloitre, M., Garvert, D. W., Weiss, B., Carlson, E. B., & Bryant, R. A. (2014). Distinguishing PTSD, complex PTSD, and borderline personality disorder: A latent class analysis. European journal of psychotraumatology, 5(1), 25097. Web Articles: The movie Tangled provides many excellent examples of what it feels like to live in the “fog” of emotional abuse. In the song “Mother Knows Best,” Mother Gothel says: “Go ahead and leave me, I deserve it Let me die alone here, be my guest When it's too late, you'll see, just wait Mother knows best.” Survivors of emotional abuse, particularly parent-inflicted emotional abuse, often resonate strongly with Tangled. If you have seen the movie, you know Rapunzel is fearful of leaving her tower. Mother Gothel has instilled fear of the outside world in Rapunzel, and she has also instilled a sense of obligation for Rapunzel to stay to demonstrate love and loyalty to Mother Gothel. The fear is twofold: the outside world has been misrepresented, and even if it had been represented accurately, Rapunzel would be unlikely to leave out of her sense of obligation to her mother. Mother Gothel is aware of Rapunzel’s empathy and compassion, and she takes advantage of these qualities by pointing out how Rapunzel will “hurt” her mother if she leaves home. We see the guilt play out later in the movie when Rapunzel leaves her tower and discovers the outside world is not as terrifying and evil as expected. Unfortunately, even as Rapunzel enjoys her adventures and has new experiences away from her mother, Mother Gothel is emotionally present. Most survivors of emotional abuse can relate to this: being physically away from the perpetrator does not automatically break the cycle. We see Rapunzel wrestle guilt and obligation, vacillating between euphoria and regret, stating “This will kill her!” and sobbing because she feels so guilty. As a side note, Rapunzel is 18 years old in the movie- legally an adult. Emotionally abusive parents rarely recognize their children as adults, regardless of age. The FOG Cycle Defined

The “fear, obligation, guilt” cycle was first defined by Susan Forward and Donna Frazier in their book Emotional Blackmail. The “FOG” is an appropriate acronym because it captures the confusing, murky feelings experienced when we are experiencing emotional abuse.

The fear goes both ways. Typically, the perpetrator is fearful of not getting what they want. Often, the behavior is coming from a deep fear of abandonment. That said, people can deeply fear abandonment and choose NOT to harm their loved ones. There is never an excuse for abusive behavior, and you have done nothing to deserve this behavior. Because the perpetrator fears losing you, they will often project that fear onto you. In Rapunzel’s case, Mother Gothel is dependent upon Rapunzel for eternal youth and beauty, so she is fearful of losing Rapunzel. Instead of being honest about her motivation for needing Rapunzel around, Mother Gothel instead instills fear in Rapunzel. She tells Rapunzel the world is scary and that Rapunzel is too weak and dumb to handle it. When we hear these messages over and over, we begin to believe it.

Family abuse is particularly insidious because we are bombarded with messages implying obligation. Most major religions have passages about honoring parents, holding family in high regard, etc. There is a stigma associated with estrangement. Most people feel some level of obligation to have relationships with family members. Perpetrators of emotional abuse will lean into the sense of obligation you may be feeling and remind you that you “owe” things to them simply because they raised you or are related to you. News flash: being on your family tree is not a free pass to harm you. And besides, if their supposed reason for treating you this way is that they love you, why do they want you to live in constant fear, obligation, and guilt? That is not love.

Guilt is not always a bad thing. It can remind us we have gone against our own values. The guilt in the FOG cycle, however, can keep us stuck in people-pleasing the perpetrator. In the cycle of emotional abuse, there is rarely room for us to develop and live by our own values. Guilt is not useful when it keeps us putting aside our own needs to meet someone else’s need for control. Hope and Healing Tangled also provides an example of hope and healing. Rapunzel does and has several of the things that are useful for breaking out of the FOG cycle.

I would love to hear your thoughts about the mother-daughter relationship in Tangled. In future posts, I will dive more into the how to recognize emotional abuse, how to protect yourself, and how to heal. References Forward, S., & Frazier, D. (2019). Emotional blackmail: When the people in your life use fear, obligation, and guilt to manipulate you. Harper. Greno, N., & Howard, B. (2010). Tangled. Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures. |

AuthorI'm Easin Beck, MFT (she/they), and this is where I share my thoughts about therapy-related things! Archives

November 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed